Are films ferroelectric?

Discipline for gold nanocrystals

Photosynthetic systems

Dissecting the atom

Catalytic clues

SAXS and the water channel

Digging in the dirt

Folding Protein Sensors

X-ray movies

Are films ferroelectric?

David Bradley is currently working with Argonne National Laboratory on a series of articles for the annual report of the ANL's Advanced Photon Source. For December's Elemental Discoveries, I will be offering a preview of the advanced science featured in the report.

Are films ferroelectric?

Discipline for gold nanocrystals

Photosynthetic systems

Dissecting the atom

Catalytic clues

SAXS and the water channel

Digging in the dirt

Folding Protein Sensors

X-ray movies

Are films ferroelectric?

Thin films of ferroelectric material for use in future "electronic" devices

can be as thin as developers desire without loss of function according to a

synchrotron x-ray study carried out by researchers using the BESSRC/XOR

beamline 12-ID at the APS. The results show that a thin film of one

particular ferroelectric material, lead titanate, is still stable even in a

layer a mere 1.2 nanometers thin.

An

electric field can control the permanent polarization in a ferroelectric

material in much the same way that a magnetic field controls the

magnetization of a ferromagnet. Ferroelectric materials known as perovskites,

of which lead titanate is one, share their crystal structure with the

mineral perovskite, and are being keenly investigated by researchers for new

applications in microelectronics.

An

electric field can control the permanent polarization in a ferroelectric

material in much the same way that a magnetic field controls the

magnetization of a ferromagnet. Ferroelectric materials known as perovskites,

of which lead titanate is one, share their crystal structure with the

mineral perovskite, and are being keenly investigated by researchers for new

applications in microelectronics.

Ferroelectric materials are already being used in microelectronic devices,

such as non-volatile random access memory (NVRAM) that exploit

ferroelectricity to store information. An electric field would switch the

permanent polarization from one direction to the other, representing the

switch from a 0 bit of information to a 1. The development of NVRAM could

provide computers and ever-smaller portable information devices with

high-density solid-state memory that, unlike conventional RAM, do not lose

their information when switched off. The Argonne research removes a

potential limitation on how dense these devices could be.

Perovskites also have other potentially useful properties. They are

piezoelectric materials, for instance, changing shape when a voltage is

applied or generating a voltage when they are deformed. They are also

pyroelectric, producing a voltage when the temperature changes.

Electronically controlled switches, valves, pumps, and sensors in so-called

lab-on-a-chip devices, or microelectromechanical systems (MEMS), could

exploit such properties.

Technologists hoping to exploit the novel electrical and magnetic properties

of such advanced materials in thin film form have often encountered problems

maintaining the properties in very thin films. Researchers found that films

of lead titanate thinner than 100 nanometers for instance had reduced

polarizability and sometimes exhibited no ferroelectric behavior at all. If

this problem proved to be the result of a fundamental incompatibility

between ferroelectricity and reduced thickness, it might present a lower

limit on the size of microelectronic components based on such materials.

Researchers from the Materials Science Division, at Argonne National

Laboratory, and the Department of Physics at Northern Illinois University in

DeKalb, were not convinced that the size effects seen in previous studies

would arise in all ferroelectric samples. It can be very difficult to

separate the effects of true size dependence from those of uncontrolled

experimental variables such as stress and composition that can vary with

sample size, team leader Brian Stephenson explains. Recent theoretical

calculations carried out by other researchers had also predicted that

perovskite films would still have ferroelectric properties even in thin

films just a few nanometers thick.

The Argonne and Northern Illinois team set about making detailed

experimental observations that would unambiguously settle the long-standing

question of the thickness limit for ferroelectricity. The team used

metalorganic chemical vapor deposition to grow thin layers of the perovskite

lead titanate on single crystals of strontium titanate. By carrying out

x-ray scattering experiments during the deposition process they were able to

control the thickness of the layer very precisely to an integer value of the

crystal's so-called unit cell. Using this in situ approach and the

high-brilliance synchrotron x-ray beam from the APS, the team obtained

accurate data from high-quality samples as thin as one unit cell.

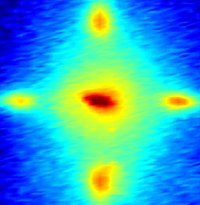

In these thin films, the ferroelectric phase forms in nanometer-scale

stripes of alternating polarity which produce characteristic signals,

satellite peaks, in the x-ray scattering results. The researchers used these

satellite peaks to identify the ferroelectric phase. Fig. 1 shows the

scattering pattern from a 3 unit cell (1.2 nanometer) thick film; it reveals

that it is ferroelectric. The team found thinner (2 and 1 unit cell thick)

films to be non-ferroelectric. This tiny thickness limit for

ferroelectricity bodes well for making sub-microscopic layers for use in

various novel applications, say the researchers.

Source: Dillon D. Fong1, G. Brian Stephenson1, Stephen K. Streiffer1,

Jeffrey A. Eastman1, Orlando Auciello1, Paul H. Fuoss1, and Carol Thompson2,

"Ferroelectricity in Ultrathin Perovskite Films," Science 304 (5677),

1650-1653, 11 June 2004).

Back to the December elemental discoveries index page