John Barry famously wrote the classic James Bond movie scores. But, the “James Bond Theme”, the guitar-led main signature, which has featured in every Bond film since Dr. No in 1962 was composed by Monty Norman. Barry, of course, utilised his own arrangements of this piece as a kind of 007 fanfare and for the seminal gun barrel sequence in many of the Bond films.

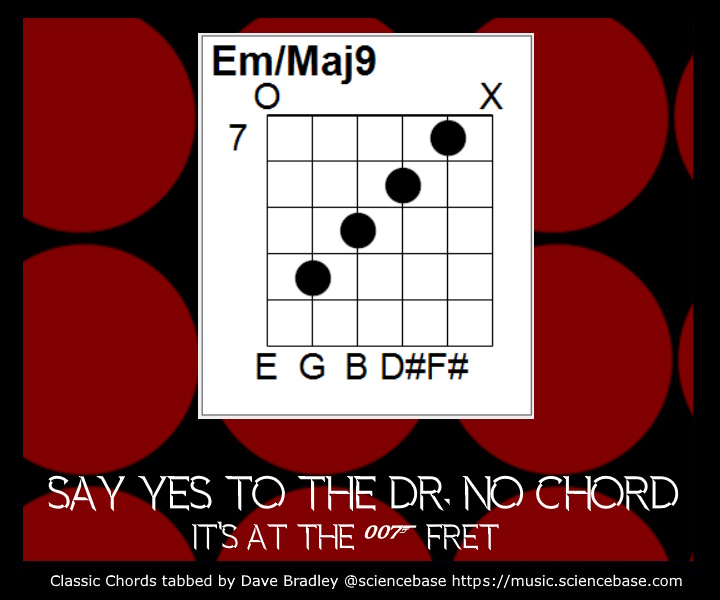

The guitar motif in the original was recorded by guitarist Vic Flick on a Clifford Essex Paragon Deluxe through a Fender Vibrolux amplifier. Apparently, Flick was paid £6 for the session, about 100 quid in today’s money. At the end of the tune there is a famously suspenseful guitar chord which makes full use of that Vibrolux. The chord in question is an E-minor/major-9 chord, sometimes styled Emin/Maj9. The E-minor triad is made up of the root 1st, minor 3rd, and the perfect 5th notes of the E-minor scale, namely E-G-B. To make the major-ninth chord, you add the major 9th interval, namely the F#. But of course, to get there you have to go via the major 7th, which is the D# of the E-minor scale.

This is a four-finger shape, a diagonal across the fretboard from the seventh fret on the B-string to the tenth fret on the A-string when playing in standard EADGBE tuning on a six-string guitar. The bottom-E string is open, the top E is muted. Strummed fairly slowly from low string to high with a pick and a lot of vibrato from the amp, gives us the dramatic arpeggio that is essentially the closure of the James Bond musical signature.

Now, at this point, if you have a fair musical ear, you might be thinking the sound of that chord is rather familiar from another jazz tune used in the movies. And, you’d be right, the very same min/maj9 type chord is used with a descending glissando at the end of the Henry Mancini theme to The Pink Panther (1963). Perhaps this was a little musical joke on the part of Mancini who would, of course, be very familiar with the work of Norman and Barry.

More Classic Chords to be found here.