Scientists sometimes take magnetism for granted. But some materials behave badly and scientists funded by the UK’s Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) are trying to find out why. They are looking at the conventional wisdom of modern theories and finding it does not always stick to exotic magnets.

Scientists sometimes take magnetism for granted. But some materials behave badly and scientists funded by the UK’s Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) are trying to find out why. They are looking at the conventional wisdom of modern theories and finding it does not always stick to exotic magnets.

Scientists from archaeologists to zoologists are attracted to magnetic measurements. Archaeologists use magnetic artefacts to date sites, while a zoologist might be investigating the effects of magnetism on bird brains. Magnetism is fundamental to science, but despite their ubiquity scientists still cannot fully explain magnetic materials.

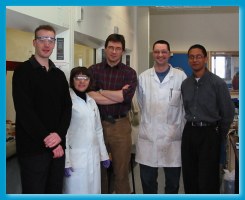

Professor of Solid State Chemistry at Edinburgh University, Andrew Harrison hopes with the help of EPSRC funding to get inside some exotic magnets, which could provide insight into more common magnetic materials and ultimately help in the design of computer memory and electrical devices. “The study of the fundamental properties of magnets gives us valuable insights into the principles that govern the structure of solids,” he explains, “This has implications that stretch beyond magnetism and into superconductivity.”

The conventional picture of a magnet says each atom in a material acts like a tiny magnet. The magnetic moment, or direction of the North-South divide on the atoms line up parallel (in permanent ferromagnets like iron) or anti-parallel in an up-down arrangement in antiferromagnetic materials, such as manganese oxide. “The reason why such materials behave this way,” says Professor Harrison, “is that below a certain critical temperature the magnetic moments ‘freeze’, or become locked in position.” For an iron magnet this critical temperature is well above room temperature but for other materials they have to be cooled near to absolute zero before they become magnetic. The picture was fairly simple until high-temperature cuprate superconductors were discovered and started throwing up strange results. For instance, some of these materials, at first sight seemed not to have frozen magnetic moments. Such findings inspired researchers to seek new understanding of magnetic materials.

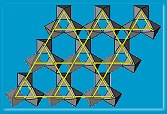

Because the magnetic moments in some superconducting magnets were very small, quantum fluctuations in their orientation overpower the usual forces that normally lock the magnetic moments in place. In the case of lanthanum cuprate, this is not quite enough to upset the conventional picture but a new ingredient – frustration – changes completely the conventional picture. Frustration is found in materials where the magnetic moments are on a triangular rather than a square lattice. “You cannot physically align all the moments antiparallel with their neighbours!” says Harrison. In such a ‘frustrated’ lattice, the conventional forces between magnetic moments are much reduced and the quantum fluctuations are more influential. This kind of magnet may never freeze and the material fluctuates between different states with the moments twitching between the sides of the triangles. The result is that the material exists as a “spin fluid” and such materials could help explain magnetism and possibly superconductivity.

According to Harrison, however, materials that have a small magnetic moment in a frustrated lattice are very rare and have proved difficult to synthesize. “Such a material is one of the Holy Grails in this area of science” he muses There are many materials with triangular lattices, such as vanadium(II) chloride, but they have conventional magnetism. “The challenge is to swap the elements such as vanadium, which have relatively large atomic moments, for magnetic copper ions, which have small atomic moments, while retaining a triangular lattice. So far the wrong lattice forms,” adds Harrison, “It’s as if nature doesn’t want to produce such a material with this kind of unstable ground state, what happens is that the magnet distorts to some other form as it cools down.”

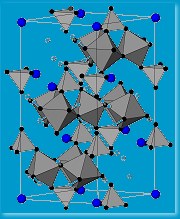

Harrison and collaborators have tried an alternative material type over the last few years. A material of chemical formula ABO2 (A and B are two different metals, O2 is oxygen) can crystallize with the rock salt, sodium chloride NaCl, structure but instead of Na-Cl-Na-Cl? it would contain A-O-B-O-A-O? making a triangular lattice. If A is magnetic and B non-magnetic, as in NaTiO2, one might be able to make a frustrated magnet. Making this material was a huge challenge but eventually Harrison’s collaborators Matt Rosseinsky (Liverpool University) and Simon Clarke (Oxford University) succeeded. Unfortunately, on cooling below its critical temperature, the atoms in the initially triangular lattice layers, jostled each other and the structure distorted. “The strategy of simply knowing which materials might produce the right lattice structure does not always produce a positive result,” says Harrison.

material type over the last few years. A material of chemical formula ABO2 (A and B are two different metals, O2 is oxygen) can crystallize with the rock salt, sodium chloride NaCl, structure but instead of Na-Cl-Na-Cl? it would contain A-O-B-O-A-O? making a triangular lattice. If A is magnetic and B non-magnetic, as in NaTiO2, one might be able to make a frustrated magnet. Making this material was a huge challenge but eventually Harrison’s collaborators Matt Rosseinsky (Liverpool University) and Simon Clarke (Oxford University) succeeded. Unfortunately, on cooling below its critical temperature, the atoms in the initially triangular lattice layers, jostled each other and the structure distorted. “The strategy of simply knowing which materials might produce the right lattice structure does not always produce a positive result,” says Harrison.

“With our EPSRC grant we are setting our own agenda as chemists, so instead of saying, ‘right nature gives us these materials to work with’, we could try and direct the lattice’s architecture by choosing chemical groups, or ligands, to join the metal ions.” One approach was to build a template that would bind to three metal ions, but not only that it would have to allow the magnetic moments of the metal atoms to couple with each to produce a magnetic material despite their being locked in a triangular lattice.

Working with chemist Neil Robertson the team is trying to design a ligand for the job. They are exploring hexathiabenzene – six-carbon rings with sulfur atoms attached to each carbon. Pairs of sulfur atoms can grab metal ions like pincers, so each hexathiabenzene links three metals together giving a triangular building block for the lattice. Smearing of the electrons – delocalization – through the benzene ring then provides the machinery for magnetic coupling between building blocks. “Although there is an element of design in this, there is also an element of luck,” says Harrison. The team is now investigating what happens when hexathiabenzene templates a copper or cobalt structure, but he admits, “We are still just finding our way around what works, designing a material is a black art.”

The team has a couple of likely products – magnetic materials with what they hope is a triangular , frustrated lattice, which will make them behave as spin fluids. The problem remains that these materials form only fine powders, which means no conclusive crystal structure. The other problem they are yet to overcome is that for their materials that critical temperature is a rather chilly five degrees above absolute zero. “The long-term challenge of building molecular magnets that might have technological applications remains a distant target,” explains Harrison. But, while that remains so, they are developing interesting structures that are helping them probe the inner mysteries of magnetism. “Our and other studies might conceivably lead to new generations of functional magnetic materials, for computing and other applications, but I’d be wary of saying it’s just around the corner because it isn’t!”

, frustrated lattice, which will make them behave as spin fluids. The problem remains that these materials form only fine powders, which means no conclusive crystal structure. The other problem they are yet to overcome is that for their materials that critical temperature is a rather chilly five degrees above absolute zero. “The long-term challenge of building molecular magnets that might have technological applications remains a distant target,” explains Harrison. But, while that remains so, they are developing interesting structures that are helping them probe the inner mysteries of magnetism. “Our and other studies might conceivably lead to new generations of functional magnetic materials, for computing and other applications, but I’d be wary of saying it’s just around the corner because it isn’t!”

Nature is not entirely mean. The magnetic jarosite minerals used as rich orange-red pigments and cosmetics for millennia contain iron. Harrison spotted the parent compound, potassium hydroxy iron sulfate, as containing a frustrated crystal lattice while still a post-doctoral researcher in Canada.

He and Andrew Wills of the Laue-Langevin Institute and colleagues, have since studied natural and synthetic jarosites from hundreds of rock samples. “We’ve also adapted the ‘natural preparation’ to include ions not commonly found in nature,” says Harrison. The resulting “spin glasses” are providing insights into magnetic phenomena.

By the way, if you want an answer to the question, “is there a material that blocks magnetic forces?”, check out the SciObs blog, the succinct answer is no.