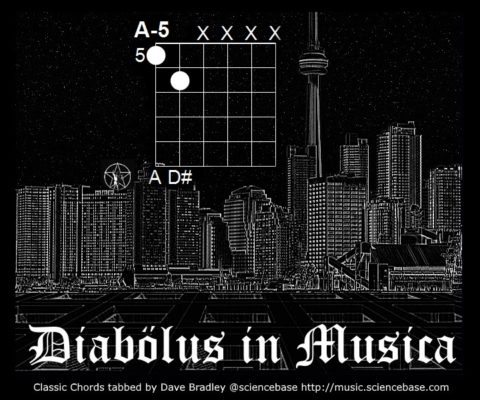

Strictly speaking this classic chord isn’t a chord at all, it’s an interval, the gap between just two notes rather than at least three different notes played together. The interval in question is often described in Western music as “dissonant” and perhaps because of the beating of the harmonics of the two notes against each other (constructive and destructive interference) it has been various labelled the devil’s interval, or more archaically, diabolus in musica. Moreover, it’s often been banned and at the very least lambasted over the centuries in many different realms of music.

The devil’s interval is two bits of what technically we refer to as a tritone. A jump from a root note, up a whole tone and then up a whole tone again, so F to G, G to A, and finally A to B. The leap from F to B is quite dissonant.

In the right hands, it can add an electric frisson to a piece of music. Think of the intro to the Rush instrumental YYZ from the 1981 Moving Pictures album. The guitar pattern played staccato in 5/4 time oscillates between F# and C (the tritone being F#-G#, G#-A#, A#-C) and represents the Morse Code for YYZ (Toronto Airport’s call sign). Similarly, the Blue Oyster Cult song Workshop of the Telescopes from their eponymous 1972 debut album, uses the devil’s interval A-D#.

Although odd, almost occult, importance has been attached to this interval, fundamentally (pardon the pun), it’s just an augmented fourth or a diminished fifth. Picture the scale of C major:

Where would rock and blues be without the 7ths (which of course are flat relative to the major scale. Look at CDEFGABC again, 7th note would be a B, but it’s down a semitone, so flat, in the (dominant) 7th. In the chor of C major 7, it stays as a B and has a much softer, almost summery sound, relative to the grittier dominant 7th with its devil’s interval.

Rush use the clash of a tritone in several songs, the intro to Between the Wheels has one with a F#11 chord resolving to an Am (both have a D note in the bass, so they’re more correctly, Dm13 and Am(add4), respectively.

Neither Rush nor BOC were being original in using this interval it had been around music for centuries, stirring passions and summoning the devil. Wikipedia has more details and more examples from musical history. In pop and rock music George Harrison uses tritones on the downbeats of the opening phrases of The Beatles’ songs “The Inner Light”, “Blue Jay Way” and “Within You Without You”, to create musical suspense resolution and of course, the opening riff of that most classic of heavy rock songs, Jimi Hendrix’s Purple Haze uses the very same interval before leaping into the Hendrix Chord (Classic Chord #3). The opening of Maria, from West Side Story too.

Oh, almost forgot, here’s the interval in action, with me playing a version of the YYZ intro: