Airport X-ray security body scanners are anything but risky business. Indeed, you will be exposed to the same dose of ionising radiation in just two minutes of your flight once you’re at high altitude. So, an 8-hour flight is equivalent to having 240 full-body scans. They reckon you’re well within safety limits at having 5000 scans a year, but that equates to only about 20 8-hour flights.

Airport X-ray security body scanners are anything but risky business. Indeed, you will be exposed to the same dose of ionising radiation in just two minutes of your flight once you’re at high altitude. So, an 8-hour flight is equivalent to having 240 full-body scans. They reckon you’re well within safety limits at having 5000 scans a year, but that equates to only about 20 8-hour flights.

Frequent flyers be warned: every time you climb aboard one of those jet-powered metal tubes and take to the air you are being bombarded with cosmic rays. The term cosmic rays is something of a misnomer as there aren’t really any rays present, that’s purely historical, cosmic rays are composed of high-energy sub-atomic particles, mostly protons (89%), 10 are helium nuclei (better known as alpha particles) and the remaining 1% are electrons (beta particles) and other spurious entities such as antimatter particles.

These cosmic particles can have energies 7 or 8 orders of magnitude greater than the energies produced by our particle accelerators here on earth. The earth’s atmosphere and magnetic field does deflect much of the cosmic bombardment so that life can survive, but, as I said frequent flyers (which includes pilots and air crew) can experience double the dose of ionising radiation of those whose feet stay firmly on the ground.

Airport X-ray scanners generate not cosmic particles, but X-rays, but to the atoms and molecules from which we are made it is the energy that they carry not their physical nature that matters. X-rays and cosmic particles will ionize atoms and molecules, once ionized these atoms and molecules are highly unstable and can fall apart or react with other nearby atoms and molecules to generate new ions. If the molecules in question are proteins this can lead to the breakdown and death of the cells using those proteins. Damage the DNA and the cell might die or it might become cancerous, replicating endlessly without the usual constraints.

Of course, we could spend hours debating the relative risk, you might even think about calling me on your mobile phone with worry (they don’t produce nor receive ionising radiation). But, for many people the high-altitude flight and the pointless X-ray body scan at the airport are often followed by two weeks lying almost naked on a hot beach during the daylight hours to expose one’s skin to hour upon hour of ultraviolet radiation and evenings are spent smoking cigarettes and drinking copious amounts of alcohol. There’s undeniable risk and then there’s risk you can deny if it would spoil your holiday to admit it exists…

Interestingly, Samanda Correa of the National Nuclear Energy Commission in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and colleagues have used a statistical method known as a Monte Carlo simulation to calculate the change in risk of developing cancer associated with exposure to X-ray body scanners. The team points out that these scanners while well known for their use in airports as an anti-terrorism measure are also widely used in prisons to combat smuggling. Their research suggests that one would need to have 130 scans to be exposed to 0.25 millisieverts of ionising radiation, which is considered the annual safe limit for members of the public. The increase in cancer risk for just a handful of scans per year is very, very low. They say it only becomes significant for those having dozens of scans annually, but even then it is a small increase.

I still suspect the sunburn, the booze and the cigarettes will do you in before the X-ray scanners get you…

Samanda Cristine Arruda Correa, Josilto Oliveira de Aquino, Edmilson Monteiro de Souza, & Ademir Xavier da Silva (2012). Evaluation of the dose and of the risk of cancer induction associated with the use of transmission X-ray body scanners using the Monte Carlo MCNPX code Int. J. Low Radiation, 8 (5/6), 340-354

Samanda Cristine Arruda Correa, Josilto Oliveira de Aquino, Edmilson Monteiro de Souza, & Ademir Xavier da Silva (2012). Evaluation of the dose and of the risk of cancer induction associated with the use of transmission X-ray body scanners using the Monte Carlo MCNPX code Int. J. Low Radiation, 8 (5/6), 340-354

If you are a working scientist, a recovering scientist, a revolutionary, or simply a geek looking for new innovations, take a look at Marblar. They’re creating a community to open up the process of invention and finding the right home for those inventions.

If you are a working scientist, a recovering scientist, a revolutionary, or simply a geek looking for new innovations, take a look at Marblar. They’re creating a community to open up the process of invention and finding the right home for those inventions.

Airport X-ray security body scanners are anything but risky business. Indeed, you will be exposed to the same dose of ionising radiation in just two minutes of your flight once you’re at high altitude. So, an 8-hour flight is equivalent to having 240 full-body scans. They reckon you’re well within safety limits at having 5000 scans a year, but that equates to only about 20 8-hour flights.

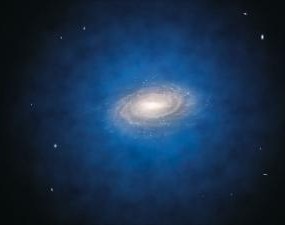

Airport X-ray security body scanners are anything but risky business. Indeed, you will be exposed to the same dose of ionising radiation in just two minutes of your flight once you’re at high altitude. So, an 8-hour flight is equivalent to having 240 full-body scans. They reckon you’re well within safety limits at having 5000 scans a year, but that equates to only about 20 8-hour flights. Dark matter might be found in hornets’ nests and cans of worms but not necessarily in the real world of cosmology and science. I recently reported on the work of Christian Moni Bidin which reveals serious discrepancies in science’s claims for the existence of

Dark matter might be found in hornets’ nests and cans of worms but not necessarily in the real world of cosmology and science. I recently reported on the work of Christian Moni Bidin which reveals serious discrepancies in science’s claims for the existence of  Over the years there has been a lot of tomato talk, about how lycopene, the red pigment found in this fruit (yes, it’s definitely a fruit, it’s got seeds), could ward off cancer, specifically prostate cancer. It has also been linked to protecting us from cardiovascular disease, per the common discussions about the so-called Mediterranean diet. It is not a panacea and tests and trials have been small-scale. Nevertheless, as with the likes of that other infamous compound, resveratrol found in red wine, researchers are keen to demonstrate a link with their particular natural chemical and disease prevention.

Over the years there has been a lot of tomato talk, about how lycopene, the red pigment found in this fruit (yes, it’s definitely a fruit, it’s got seeds), could ward off cancer, specifically prostate cancer. It has also been linked to protecting us from cardiovascular disease, per the common discussions about the so-called Mediterranean diet. It is not a panacea and tests and trials have been small-scale. Nevertheless, as with the likes of that other infamous compound, resveratrol found in red wine, researchers are keen to demonstrate a link with their particular natural chemical and disease prevention.